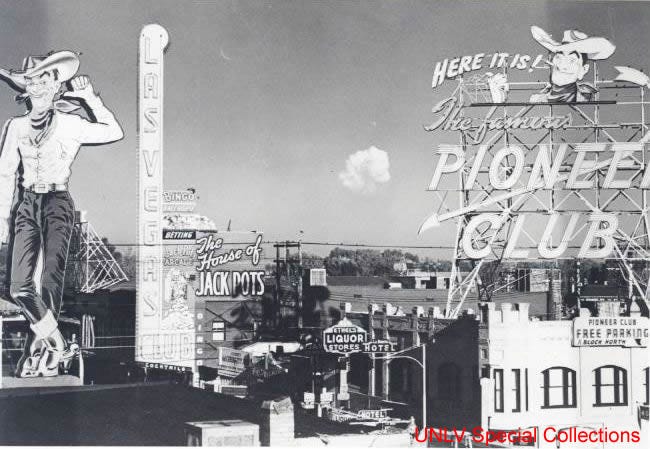

LAS VEGAS — There is no dateline more significant that has prefaced the output of my half century of student and professional journalism, spanning hundreds of cities around the world, than this one. Yes, I’m getting old and I started young. My first bylines appeared in The Lancet, the school paper of Fremont Junior High here, and as the youth recreation columnist for The Las Vegas Israelite.

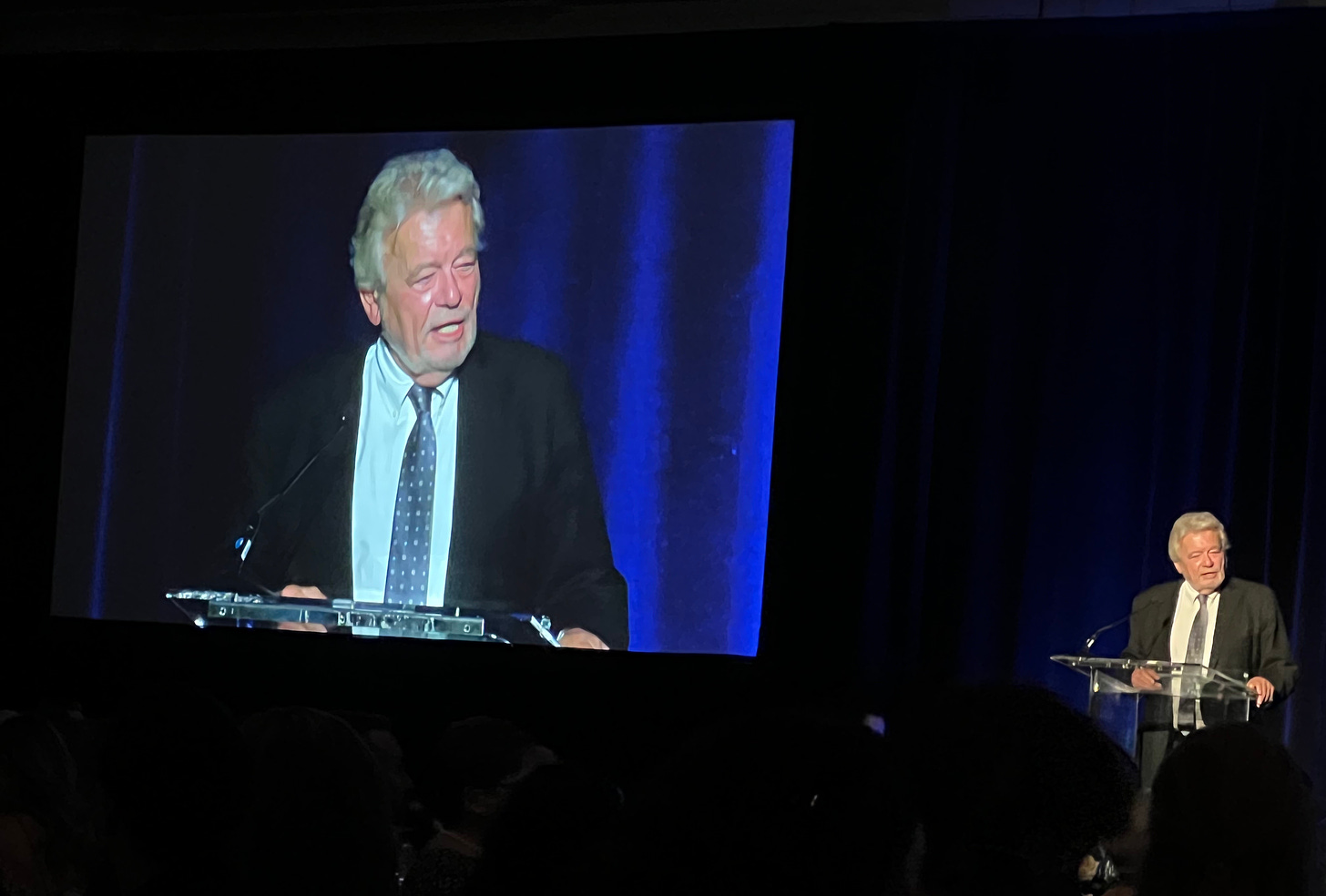

This past weekend I returned to where I spent what I jokingly refer to as my deformative years to be inducted into the Nevada Broadcasters Hall of Fame in a Saturday night ceremony in the ballroom of the Four Seasons Hotel on the Las Vegas Strip.

The headliner of the event was my former KLVX-TV news colleague, George Knapp, a local legend and nationally recognized reporter of all things extraterrestrial, accepting the association’s lifetime achievement award,

George, who was driving taxis and with no professional journalism experience, walked into Channel 10 around the same time I was hired. The news director, Liz Vlaming, unbeknownst to us, had a track record of taking risks on unconventional hires. Soon, George and I were on board.

Channel 10 was the PBS affiliate, not really in competition with the three commercial TV newsrooms in town. What our couple of weekly news and public affairs programs lacked in cosmetic polish, we compensated with in scrappy and in-depth coverage of stories that received scant air time on the network affiliates. We reported about Colorado River water rights (currently a critical issue in Western states) and investigated regional cancer deaths from nuclear fallout. We scrutinized controversial decisions of gambling licenses that uncomfortably brought together mob figures (Tony ‘The Ant’ Spilotro and Frank ‘Lefty’ Rosenthal) with celebrities (Frank Sinatra) and state regulators, some of whom were aspiring politicians (Harry Reid). They’re all dead now. But I imagined their ghosts in the Four Seasons ballroom for the ceremony which had on stage Knapp, myself and another former Channel 10 colleague, Mitch Fox, who is now president of the state broadcasters’ association. In the audience were some prominent figures from Nevada politics, including 86-year-old Richard Bryan, who is a former governor and U.S. senator, and Shelly Berkley, a former House member and current Las Vegas mayoral candidate.

George alluded to Nevada’s colorful characters of decades past and the lure of Las Vegas for all types looking for second chances. He noted that while Las Vegas was not a big city when we began our broadcasting careers it, even then, was probably the most exciting local media market in the country.

“There’s never been a slow news day since I got here,” George told the crowd.

A benefit to beginning my journalism career as a teenager in Las Vegas in the late 1970’s was although it was indeed a relatively small media market, everybody who was anybody came through town at least once a year. The casinos lured millions of visitors annually and the gambling-infused hospitality led to an infrastructure for hosting major trade shows and conventions. Those events attracted celebrity guest speakers from the president on down. At one such industry gathering a cluster of local reporters assembled for an interaction with George H.W. Bush, then vice president. I cannot recall what question I asked him or whether his reply merited inclusion in our local newscast. But such media opportunities allowed us to fill in on-the-spot for the networks who would not send a crew unless it was known the event would be of national significance.

My radio mentor, Bill Buckmaster (subsequently a long-time public TV news anchorman and radio talk show host in Tucson, Arizona) taught me the technique of “dialing for dollars.” Our bit of news voiced around a snippet of audio tape could be fed through the phone lines to various radio networks. Back then these “wraps” could each net us $20 to $40 and if successful in feeding several networks a couple of times a week, it amounted to a respectable supplement to our meager salaries.

Hearing my voice hours later on the CBS or NBC hourly radio newscasts was a thrill and I suspect that when I began ‘stringing’ for the broadcast networks few in the audience had any idea that the reporter on the scene in Las Vegas was a teen.

The side work helped build my confidence at a young age that I could perform at the network level. Some in the industry noticed and would remember my Las Vegas reporting decades later. I never fantasized about becoming a White House correspondent. It wasn’t imaginable. If I was very lucky, I said to myself, I could dream of being a radio field reporter in a larger nearby market — such as Phoenix. Perhaps I would one day work at KNX, the highly-rated all-news radio station in Los Angeles. I thought I might, as a tourist, eventually peer through the gate of the White House from Pennsylvania Avenue, but I didn’t harbor any dream of working inside that building.

My career path began at Fremont Jr. High. Seventh graders were allowed to take one elective and I struggled to choose. There were few options – including industrial arts for the boys and home economics for the girls (it was a different era) and I contemplated selecting the boys’ class colloquially known as “shop.” My mother, rightly concerned about me handling sharp tools (I showed no potential as the handyman type despite my father’s skill as an electrician), suggested the safer journalism elective, saying: “You’re a good writer.” That was a revelation to me as my mother rarely uttered compliments. I wasn’t sure what ‘journalism’ was and when it was explained I would be able to work on the school newspaper I was intrigued.

Florence Beebe, a patient woman in her early 60’s, taught special education, typing and journalism. The journalism students sat in the typing classroom once a week. In later years, when I began working fulltime in newsrooms, I realized typing had been the most valuable skill acquired from middle school, as I watched two-fingered typists struggle with keyboards. Mrs. Beebe’s most critical contribution was letting me write while correcting grammar, improving my style and instilling the fundamentals of journalism: Who, what, where, when and why. The work as a reporter and editor on school newspapers felt natural, fun and rewarding over a five-year period -- more so than math, science or any of the attempted extracurricular activities (most unsuccessfully the Valley High School track & field team, for which I was never chosen to compete and ended up listed in the yearbook team photo as “unidentified”).

Las Vegas in the late 1970’s outpunched its weight class as a regular dateline for big news stories, at least those that could generate headlines beyond Nevada. The fodder was provided by celebrities, colorful politicians, hotel disasters, as well as mobsters and resulting bodies in the desert and other intriguing homicides. This gave fledging journalists the opportunity to cover stories more commonly experienced at the national level, to learn and make rookie mistakes that would make me a savvier reporter when I found myself, decades later reporting from Lima, Kathmandu or the White House.

Besides the organized crime skullduggery, the celebrity performers on the Las Vegas Strip, boozy conventions and shady politics, the expansive desert yielded more than murder victims. To the north of the city was the Nevada Test Site. A sprawling 1,355 square-mile federal reservation larger than the state of Rhode Island, it was best known for testing nuclear weapons. Before my family had moved to Nevada in 1971, above-ground tests had been set off on a regular basis (there were more than 100 of them), becoming a tourist attraction in Las Vegas as visitors could see the mushroom clouds rising from the north.

One of my first investigative series of reports at Channel 10 focused on the health effects of those who lived downwind from these atmospheric blasts. It was evident that Atomic Energy Commission (a predecessor to the U.S. Department of Energy) officials would wait until the winds were not blowing towards Los Angeles to explode their bombs. The radiation clouds headed towards less populated and less influential communities. It was an early lesson in what we now would call environmental justice, as the federal government sought to downplay the severity the fallout. In the late 1970’s some of those in the affected communities gathered and analyzed data linking high rates of diseases, such as acute myeloid leukemia, to the weapons tests. Subsistence farms and ranch had suffered exposure and locals had consumed that contaminated beef, milk and vegetables. Between 1951 to 1962 the radiation that went into the atmosphere from those tests was equivalent to 20 times the amount released during the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear accident in Ukraine.

The single-worst episode, little known even now to the American public, occurred on May 19, 1953 part of what was Operation Upshot-Knothole, testing a new more efficient hollow-core nuclear bomb design. The blast created more fallout than had been anticipated. Carried by the strong early-morning winds, the radiation blanketed the town of St. George in Utah which was inhabited by about 4,500 people, most of them Mormons.

“Dirty Harry,” as the bomb test came to be known, had a yield of 32 kilotons and was responsible for half of the total radiation the public within a 300-mile radius of the test site was exposed to during the entirety of testing in Nevada. The radiation levels maxed out Geiger counters in the Utah town but almost no one was advised to take shelter. Schoolchildren were out on a playground an hour after the radiation had settled. The AEC, amid growing concern, issued an emergency film to try to convince the public they were not in danger.

The AEC, however, did not take preventive measures for future tests, such as warning those downwind to stay indoors immediately following a detonation or not to consume local vegetables or milk for a period of time, although some government health experts knew this should have been recommended.

A postscript to the ‘Dirty Harry’ test: A year later a major Hollywood movie was filmed for several weeks outside of St. George, on soil contaminated by the fallout from that test and nearly a dozen others that had been conducted in 1952. The film, titled “The Conqueror,” co-produced by Howard Hughes, starred John Wayne and focused on a 13th century war between Genghis Khan and Tartars. It is considered one of the worst movies of the 1950s. Wayne, a heavy cigarette smoker, would die of stomach cancer at the age of 72. Nearly half of the cast and crew of 220 would develop cancer by 1980 and 46 were dead of the disease by that time.

As I would find out, subsequently covering a federal trial about another nuclear test, it is difficult to definitively conclude any individual exposure is responsible for a cancer case decades later, but when the epidemiological statistics indicate an anomaly, it should raise concern among journalists and public health officials.

Federal officials continued to resist taking responsibility for cancer deaths from the atomic tests when I began dealing with them decades later, an early lesson in obfuscation with legal and lethal consequences.

By the time I began my journalism career, the nuclear tests had gone underground. The last atmospheric U.S. nuclear test had been conducted on November 4, 1962.)

The ‘middle-of-the-road’ music format radio station where I worked for several years, KORK AM, had a three-person news team, something of a rarity these days except at a few major market all-news radio stations. Bill Buckmaster and his team (including Jackie Glass, who would become a district court and syndicated TV judge) took reporting seriously and it was an excellent training ground where I was given considerable responsibility for field reporting, as well as producing and anchoring newscasts. Every time there was a nuclear detonation at the Nevada Test Site, the U.S. Department of Energy would provide a live audio feed for local radio stations to warn residents and tourists about imminent tremors, the effects of which were magnified in the upper reaches of the expanding number of high-rise hotel/casinos on the Las Vegas Strip.

From one of those underground tests, on May 10, 1978, I learned to be skeptical regarding what government officials might claim. The nuclear test was code-named Transom and the weapon was buried at 2,100 feet. The test — part of the Energy Department’s Operation Cresset, which consisted of 16 announced and seven secret detonations in the Nevada desert — was expected to have a yield of 20 to 150 kilotons, powerful enough to shake buildings in Las Vegas. KORK and other radio stations aired the countdown seconds before 8 a.m. Energy Department spokesman David Jackson then described dust rising from ground zero and a few seconds later, feeling the rocking motion at the command post.

At our radio station, Buckmaster’s news team swung into action to gather reaction, including from the Top of the Strip restaurant’s legendary maître d’ August Nogar at the Dunes Hotel & Casino. He was always flustered by the atomic blasts. Nogar would reliably tell us how the seismic swaying made him nauseous. His flamboyant commentary made for somewhat hilarious soundbites which Buckmaster, for years, had supplied to various radio networks in the United States and around the world, earning a modest outcome income – part of our “dialing for dollars” side gig. On that day the Dunes maître d’ was uncharacteristically calm, intoning he certainly did not detect any movement atop the 24-story tower. Neither could we find anyone else who experienced a shaking sensation. This was unprecedented. Based on this reporting of an apparent non-event, the Energy Department spokesman was compelled to belatedly admit the nuclear test was a dud and he had been dutifully reading off a script, not describing in the countdown broadcast what he had actually seen and felt (which was nothing). “National security precautions,” he said, prevented him from explaining why Transom had failed to detonate.

This was an early and important tutorial as a journalist that government agencies and public officials sometimes lie. And it was a revelation that helped me build healthy skepticism when government officials told me and other reporters to believe their words and statements, not other evidence we had gathered. This is now referred to as gaslighting, a term taken from a 1944 movie, starring Charles Boyer and Ingrid Bergman, in which the male protagonist convinces his wife she is imagining things that are actually happening—including the dimming of the home’s gas lights—resulting in convincing her she had gone insane.

A far more serious incident at the Nevada Test Site had occurred some years before the faked dud test. This was the 1970 Baneberry incident – prior to the start of my journalism career. Nearly a decade later the ramifications of that flawed nuclear test played out in a federal courtroom in Las Vegas and the case would continue through the appeals process until 1996.

The 41-day Baneberry trial in 1979 was the first big courtroom case I covered extensively. The experience, while no substitute for a proper legal education, did provide a solid grounding in the rules of evidence and on-the-job training about how to quickly transform highly technical testimony into understandable daily news reports for a non-scientific audience.

Baneberry is a poisonous desert fruit, an ironic code-name government scientists surely regretted. Shortly after sunrise at Yucca Flat on December 18, 1970, something unplanned occurred 900 feet below the desert surface, 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas. The nuclear device, like all others the United States and the Soviet Union detonated since 1963 when an atmospheric test ban had gone into effect, was supposed to contain its radioactive force underground. The blast, less than the equivalent of 20,000 tons of TNT, disturbed an adjacent pocket of water, creating a 100-yard-long surface crack, sending a toxic cloud 8,000 feet above ground. About 900 Nevada Test Site employees were in the area, including two Wackenhut security guards, Harley Roberts and William Nunamaker. Both would die four years later of acute myeloid leukemia after being among the 86 test site workers exposed to the radioactive fallout.

The guards’ widows sued the federal government with Judge Roger Foley determining those responsible for the test blast had been negligent. Foley’s ruling would eventually be reversed on appeal with a three-judge panel in San Francisco determining the widows did not have enough proof their husbands had been harmed by the radiation exposure. The case, which the KORK news team also covered for the national radio networks, prompted congressional investigations that led to the enactment of the 1990 Radiation Exposure Compensation Act.

In June of 2022, President Biden signed into law an extension of the 2020 termination of the trust fund to pay successful claims filed in connection with work in uranium mines and processing the radioactive ore (for which the government has agreed to pay compensation of $100,000). Those found to be what the government characterizes as “onsite participants” of atmospheric nuclear weapons tests may be eligible for a one-time payment of $75,000. Civilians who lived downwind from the Nevada Test Site are eligible for a one-time lump sum compensation of $50,000 on condition they “establish a subsequent diagnosis of a specified compensable disease,” which are certain types of cancer, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

The conclusions of legal cases stemming from test detonations of atomic weapons or nuclear accidents can linger for years or decades, just like the radioactive isotopes those incidents allowed to escape containment.

There were other mysterious activities at the Nevada Test Site when I reported about it during the late 1970’s. A rancher had his land seized by the U.S. government in the interest of national security. We couldn’t get a straight answer as to why or even which federal agency was responsible. The property was near something called Area 51. For most of the 20th century it was a closely guarded secret, known to few who did not work there or have a very high government clearance.

Groom Lake, a salt flat, is at the core of this highly classified facility. I was among the few journalists in Las Vegas who became intensely curious about the desert lake in the late 1970’s. We were told it was run by the military or the CIA, depending on what source one was speaking with. It did not take a lot of digging to determine this is where spy planes were tested, modified and flown, including the U-2 and the SR-71. There were whispers of far more exotic aircraft, supposedly using extra-terrestrial technology. I was never able to make a definitive conclusion about such claimed alien influence. There was no credible first-hand witness willing to go on the record.

Knapp, who became an award-winning investigative reporter at the CBS affiliate, KLAS-TV, where he is currently the chief investigative reporter, developing a decades-long cottage industry reporting on the supposed alien connection to Area 51 and, decades later, he is still trying to solve the mysteries. Knapp is also a frequent host of the syndicated radio show Coast to Coast AM, which focuses on the paranormal.

Some U.S. presidential candidates promised to make public the government secrets about unidentified aerial phenomenon and tell us if there has been contact with aliens visiting Earth. Trump acknowledged being briefed on the topic, saying “we’re watching for extraterrestrials,” and alternatively stating he didn’t particularly believe people who claimed to have seen UFOs while he also wondered out loud if they’re real. In an interview with his son, Donald Trump Jr., the president hinted he knew more about the 1947 Roswell incident (which I also investigated in later years), stating: “I won’t talk to you about what I know about it, but it’s very interesting.”

When the FBI seized highly classified documents Trump had taken home with him to Florida after his presidency, I wondered whether any of them were about aliens.

Other former presidents have been equally reticent to reveal what they know. Having been informed of something that potentially could disrupt the social order did some presidents vow to never make the knowledge public?

Barack Obama, on a late-night talk show, said he had asked about aliens after taking office and was told the U.S. government was not keeping aliens in a lab, as has been long speculated. Obama did state what is obvious to most who have an interest in the subject – there are objects in the sky that move in an unexplainable manner. Obama’s fellow Democrat, Bill Clinton, was also known to have a significant interest in the phenomena and on a visit to Northern Ireland in 1996 stated: “If the United States Air Force did recover alien bodies, they didn't tell me about it, either, and I want to know." George W. Bush, also was asked on a late-night TV talk show about what he knew about aliens, said he would not reveal anything he had been told on the topic as president, even to his daughter who was curious to know.

Other 20th century presidents had an interest in the mystery, including Jimmy Carter, who revealed having his own close encounter and vowed never to ridicule anyone claiming to have seen a UFO. During the 1976 presidential campaign (which is when I first met him in Las Vegas), Carter promised, if elected, he would release “every piece of information” on the subject. After his victory, however, Carter reversed himself saying public disclosure might have “defense implications” and pose a threat to national security.

As George Knapp noted in his remarks on Saturday night, the UFO question is now in the mainstream (in no small part, I will point out, due to George applying journalistic scrutiny to the evidence for decades). There have been recent Congressional hearings (George was in the front row but declined to testify) and NASA just announced it is appointing a director of research for “unidentified anomalous phenomenon.”

I have no doubt that wherever this story goes will lead back here to the Mojave Desert in Nevada. A lot of secrets are still buried in the sand. Shifting winds and journalistic scrutiny sometimes expose the truth, even if it is bleached by decades of obfuscation.