The Place May Be the Same but the Name is Not

Turkey rebranding as Türkiye raises a geo-political quandary from Africa to across Asia.

Let’s talk Turkey – or shall we say Türkiye? If the capital of China is rendered as Beijing in English, should we still be ordering Peking duck? Why does Bombay chicken remain on the menu, although the city is now Mumbai? The Dutch ditched Holland in 2020 and would like English speakers to call their country the Netherlands (which they spell Nederland). Does that mean we have to tell the waiter to hold the Hollandaise sauce?

The foreign minister in Istanbul (formerly known as Constantinople), Mevlut Cavusoglu, last year said his country wanted to be known in foreign languages as Türkiye to boost “brand value.” The United Nations complied. Some U.S. government agencies, notably the Defense Department, adopted Türkiye (a critical but cantankerous NATO ally), while the State Department uses the old and the new.

Some Turkish officials have long resented their country, previously the centerpiece of the Ottoman Empire, sharing a name with a bird and an idiom that denotes a dud.

“I can’t really see anything wrong with countries wanting their names to reflect what they call themselves,” says Emily Yeh, professor of geography at the University of Colorado. “Country ‘rebranding’ is about territory, sovereignty or national identity and in that sense is radically different from corporate rebranding, which is arguably ultimately about a calculation of profit.”

For names of countries and cities abroad, U.S. government agencies rely on the Geographic Names Server, maintained by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, where the entries are refereed by the official U.S. Board of Geographic Names.

“We default on style matters, including place names, to the AP Stylebook because The Associated Press, as a cooperative of major U.S. news organizations, reflects a consensus of American journalism,” explains David Jones, deputy managing editor for the VOA central newsroom. “However, we deviate from the AP when there is a compelling case to be made. This is often because the AP audience is mainly American while our audience is everything but,” says Jones.

Journalists and diplomats still debate whether to use Burma or Myanmar, beset by civil war.

“Our official policy is that we say Burma’ but use Myanmar as a courtesy in certain communications,” Jen Psaki, then the White House press secretary, said in early 2021.

Africa has been the continent to see the greatest change as it cast off colonizers in the 20th century. You can date a globe by whether it has Upper Volta or Burkina Faso and Rhodesia or Zimbabwe (both changed in 1984), as well as Gold Coast or Ghana (1957) and Tanganyika (1961) or Tanzania (1964). Benin was once Dahomey (until 1975). Then there was Zaire from 1965 to 1977; it was and is again the Democratic Republic of Congo, moving way up the alphabet.

“If you’re an African country that's the product of colonialism and the name was imposed on you by the British [rule] or something like that, it’s totally understandable,” says Ian Johnson at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR). “But a lot of these are tinpot dictatorships just trying to burnish their nationalist credentials.”

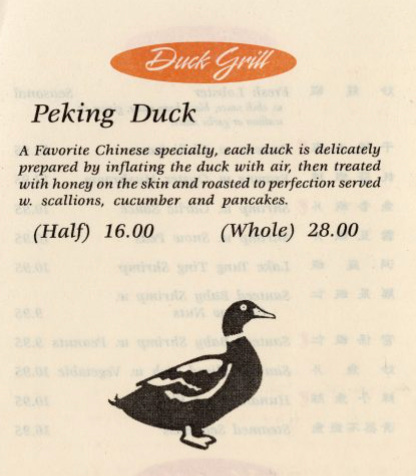

Under the king’s decree in 2008, Swaziland transformed into Eswatini. “Whenever we go abroad, people refer to us as Switzerland," King Mswati III lamented about a similar sounding landlocked country 8,500 kilometers (5282 miles) to the north.

India, seeking to cast off British and other imperial power names, created tongue twisters for speakers of foreign languages. Trivandrum was the capital of the state of Kerala. It is now Thiruvananthapuram. You can try your luck matching the correct pronunciation in Malayalam.

Madras is now Chennai; Calcutta became Kolkata; Bangalore rebranded as Bengaluru and Benares became Varanasi. Mysore, a memorable but perhaps painful name in English, is Mysuru.

But some in India assert other location name changes are meant to erase the country’s Muslim monikers from when the Mughals ruled. Case in point: Prayagraj. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist party came up with that name, referencing a Hindu pilgrimage site, to replace Allahabad.

Some local institutions continue to resist the 2019 conversion. The University of Allahabad has been called that since its inception in 1887 and is not changing.

Thailand has had a difficult time over the past century deciding whether to be known by that name or Siam. It shed Siam in 1939 only to reapply the shorter name from 1945 to 1949. It was well into the 1950s before Thailand reappeared in news dispatches from Bangkok.

In Colombo you can still drink Ceylon tea, but the country has been Sri Lanka since 1972.

What is unique about Turkey is that the government wants the world to use its Turkish spelling, if not pronunciation.

It is as if the German government proclaimed all should call the country Deutschland. Or potentially more problematic for speakers of non-tonal languages, China could insist on universal usage of its native name: Zhōngguó.

“I don't think you should start bullying NGOs, newspapers and the rest of the media to do this because it would be endless confusion to the world,” says Johnson, CFR senior fellow for China studies. “Rather than drawing us closer, it pushes us further apart.”

Johnson notes Washington does not tell the rest of the world how to spell or pronounce the United States of America. In Chinese, America is 美国 (Měiguó). By why would Americans want that changed? It literally translates as “beautiful country.” Hard to beat that branding.

China, meanwhile, wants Tibet, which it took over in 1951, to disappear and be replaced by Xizang.

“Xizang itself is a problematic term. It’s certainly not what Tibetans call themselves in their own language and so it doesn’t work as an anti-colonial strategy, though China would say it does as it doesn’t recognize itself as a colonizing power,” says Yeh, past president of the American Association of Geographers.

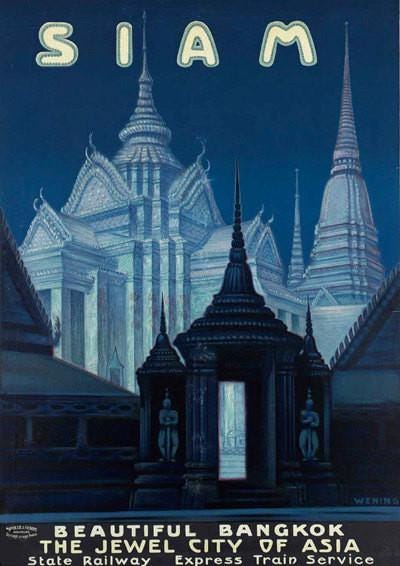

Depending on who has been in power in China, what is now the world’s most populous national capital city has morphed in English from Pekin to Peking to Peiping to Beiping to Beijing, the latter in line with the Chinese Communist Party’s preference for the pinyin script conversion system.

“It's just simply a different way of romanizing the same Chinese characters,” explains Johnson. “Ultimately, saying Beijing is no more accurate than saying Peking.”

The French continue to utilize Pékin, and the Germans, Peking.

Most English language news outlets acceded to Beijing for their datelines by 1990, the BBC being among the last holdouts. But we, for the most part, have stuck with the (Peking) duck.