Few journalists, even most of the great ones, are awarded a Pulitzer Prize. Even fewer can boast their award-winning reporting was the catalyst for bringing down a dictator. Lewis M. Simons is in that ultra-special category. In 1986, he and two colleagues of the San Jose Mercury News were the recipients of the Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting for their series of articles the previous year documenting the massive transfer of wealth from the Philippines national treasury by President Ferdinand Marcos and his cronies into luxury real estate holdings abroad.

As Lew acknowledges nearly 40 years later, his investigative reporting “played a direct role” in the People Power revolution that ousted Marcos.

The Philippines went through numerous gyrations of governance since then. Today, ironically, a Marcos is back in power. Bong Bong, the dictator’s son, is the democratically elected president.

A few years after Lew earned his Pulitzer, I met the legendary reporter at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan. He was easy to spot. The New Jersey native had a beard that was a facsimile of Abe Lincoln’s. Simons, in the spirit of Lincoln, became involved in Club politics. He was elected president and while he didn’t save a republic (after toppling a dictatorship), Lew’s leadership was credited with saving the FCCJ from financial insolvency. He also hosted for a talk at the Club an opinionated New York real estate developer who expressed appreciation for the delicious meal of rack of lamb.

Donald Trump asked the club president if the foreign correspondents also ate this well.

“Oh, sure,” Lew lied.

Most of the time he told the truth.

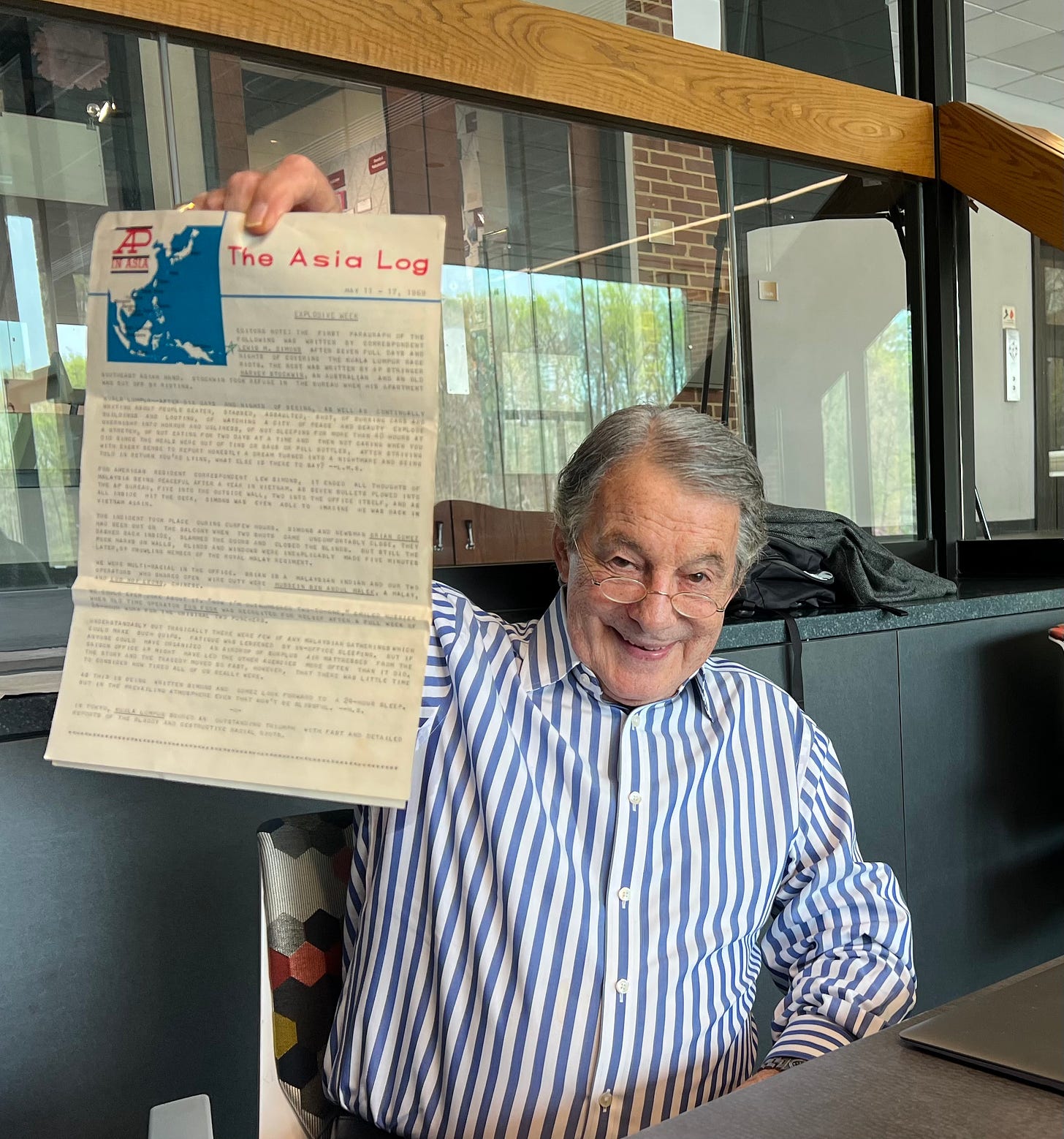

When I recently realized Lew had published another non-fiction book, this one a memoir, titled “To Tell the Truth: My Life as a Foreign Correspondent,” I not only ordered a copy but invited him to speak to my international reporting class at the University of Richmond.

On Monday, we welcomed Lew, and his wife, Carol, also a veteran journalist, to campus. Joining us for the pizza lunch discussion in the Tyler Haynes Commons Think Tank were the journalism department chair, Shahan Mufti, and one of our colleagues, Don Belt, who was an editor for some of Lew’s reporting for National Geographic.

As the Simons couple noted, they have grandchildren the age of our students. For a couple of hours, we bridged the generation gap.

What both Lew and Carol stressed were the long hours of the profession – hours that could turn into consecutive days without sleep and little to eat.

After one marathon reporting stint, during which he might have been awake for 40 hours, Lew returned to his Manila hotel to begin writing on his word processor. At some point he dozed off for an indeterminable amount of time. He woke up to see that the only text he had written: “chocolate ice cream cone.”

Lew’s career as a foreign correspondent had begun with the Associated Press in Saigon after a stint on the wire service’s foreign desk in New York.

AP figured that Simons, with his background as a Marine, could balance the anti-war tone of the dispatches of Peter Arnett. Simons went off to Vietnam a backer of the American war effort. He departed opposed to it after comparing what he experienced on the front lines with the mischaracterizations spouted by military officers at their Saigon briefings known as the ‘Five O’clock Follies.’

“That was the beginning of becoming a cynic,” he told our class on Monday.

Lew dispensed valuable tidbits to the room.

This type of front-line reporting on wars, disasters and all manner of upheaval involves “going places nobody else wants to go and sometimes places no one else can go.”

Some in our class are bilingual or multi-lingual and those language skills are “a huge leg up” when working abroad.

Lew pointed out that for fledgling foreign correspondents there are two regions ripe for exploration. “Africa is a major playground for the Chinese and the United States,” Lew noted. “Latin America is also seriously under-reported.”

Lew and Carol first met at Columbia University’s journalism school. The campus was certainly a personal and professional benefit for them. In this era, Lew questions whether the prestigious graduate degree is worth the $130,000 cost. For most graduates it might take many years, if ever, to earn that much annually if they stick to journalism.

The undergraduate students in my international reporting class are trying to weigh a different cost. Their questions to Lew and Carol primarily revolved around how to maintain a work-life balance and preserving mental health in a relentless profession.

On the work-life balance thing, “I don’t think I succeeded,” Lew bluntly acknowledged. “Maybe others have been more successful at it.”

His trait for success was “when I get on a story everything else goes away.” That included family.

Lew, fortunately, had an understanding spouse who was also a journalist, but she was left alone frequently with small children in foreign countries when the siren of breaking news sounded.

“Half of the journalists we know have been through at least one marriage and most likely two,” Carol lamented.

Carol, notably, was stranded in India in 1975. The government expelled Lew for his reporting just before the prime minister, Indira Gandhi, declared a state of emergency. He was given mere hours to leave the country and the authorities disconnected his home phone in Delhi, literally severing the line of communication between Lew and Carol.

Times have changed. Not just for trailing spouses of journalists. The business has changed. Lew talked about this, as well, and lamented that 70 percent of the population “doesn’t believe what we write, what we report.” It is OK for the public to be skeptical but to not trust journalism, “a critical pillar of democracy” is alarming.

One student rejected the notion that how to fix this is the responsibility of the generation entering journalism.

Younger people entering the industry, they're not being listened to,” she said. Older journalists just “continue to glamorize people like Edward Murrow. Like you can't do that anymore. It’s not feasible. But we're still being held to that standard.”

It is an excellent point and one that perhaps our journalism department should explore as the primary topic for a future class. Or Lew can write a book about it.

His latest book highlights a very personal story of once ignoring his mantra of “don’t put your thumb on the scale.”

It was an intervention that saved the life of a young Tibetan monk. But he crossed a line he had set for himself over a half century of reporting. In this instance “it was one of the best things I ever did in my life,” Lew said.

Read his book for the details and you will understand why the Dalai Lama wrote the foreword to it.

—

Steve Herman is the chief national correspondent for the Voice of America and an adjunct lecturer in journalism at the University of Richmond. His musings here are his own and do not reflect the views of VOA or the university.